Attachment After Trauma; When Safety and Closeness Feel Complicated

How trauma reshapes the way we connect, and how to begin rebuilding safety.

It's 2 a.m. and you're staring at your phone again.

They haven't texted back in three hours. Your rational mind knows they're probably just asleep. But your body tells a different story, chest tight, thoughts spiralling, that familiar dread pooling in your stomach. They're pulling away. They're done with me. I knew this would happen.

So you send another message. Then another. You need to know they're still there, that you haven't been abandoned, that the ground beneath you is still solid.

When they finally respond in the morning, casual, warm, completely unaware of the night you just spent, relief floods through you. For about an hour. Then something else kicks in. The closeness that felt desperately necessary last night now feels suffocating. You go cold. You pull back. You pick a fight over something small, or you ghost them for the rest of the day.

Later, you'll hate yourself for it. Why do I do this? Why can't I just be normal? Why do I ruin everything good?

But here's what's actually happening: Your nervous system isn't broken. It's doing exactly what it was trained to do when the people who were supposed to keep you safe were also the people you needed protection from. When closeness and danger got wired together in your developing brain, when love became unpredictable, when your earliest relationships taught you that connection and threat are the same thing.

This is what emotional abuse does to your nervous system, it tangles up the very wiring that's supposed to help you feel safe with other people.

You're not too much. You're not impossible to love. You're responding to an old wound that's still trying to protect you from dangers that may no longer exist.

When the People Who Should Soothe You Are the Ones Who Scare You

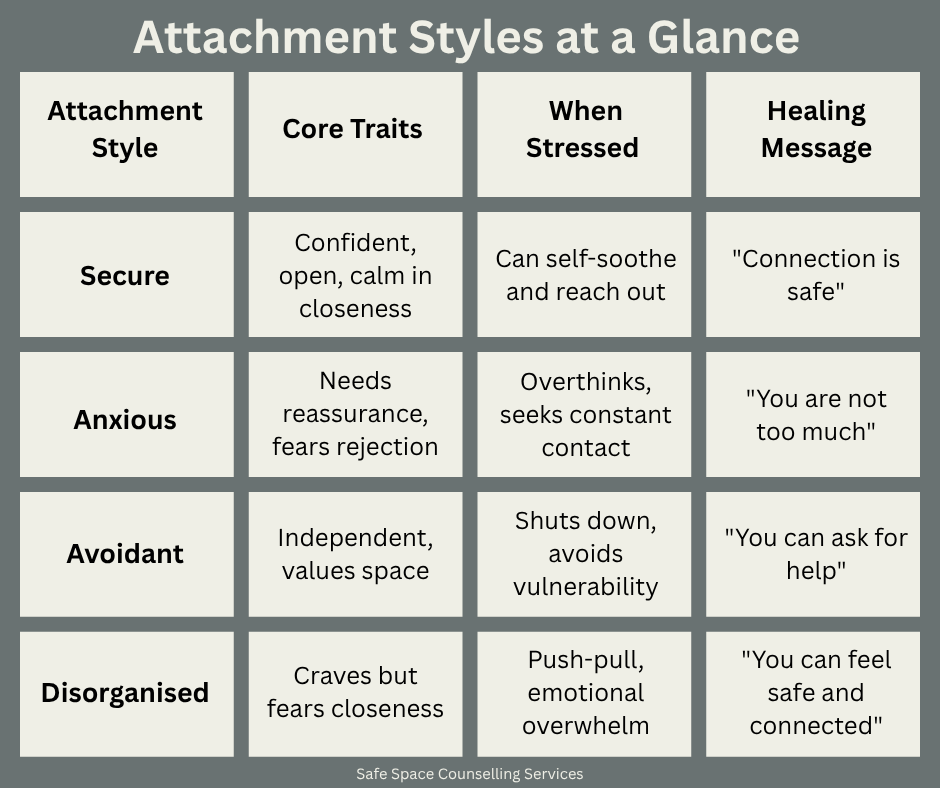

After trauma, attachment patterns don't follow the neat categories we're taught: secure, anxious, avoidant. They become fluid, contradictory, context-dependent. You might cling desperately one moment and push away the next, sometimes within the same conversation.

Your nervous system didn't learn to manage closeness. It learned to manage fear while staying close enough to survive.

If your caregiver was your main source of both comfort and terror, warm one moment, raging the next, attentive sometimes and emotionally absent others, your developing brain encountered an impossible contradiction. Distress told you to seek closeness for soothing, but that closeness activated more fear. So your attachment system splintered into competing strategies: seek and avoid, approach and flee, cling and push away.

This shows up powerfully in children of emotionally immature parents, where the very person you need for safety is also emotionally unpredictable or unavailable. Your body learned that love doesn't mean safety. And now, even in relationships where you are genuinely safe, your nervous system can't quite believe it.

The Push–Pull Pattern (When You Can't Win Either Way)

You send a message. No reply. Panic sets in immediately.

Your stomach drops. You check your phone compulsively, once, twice, twenty times. Each time you refresh, a story forms: They're losing interest. I said something wrong. They've realized I'm too much. This is the beginning of the end.

The anxiety builds until you can't sit with it anymore. You send another message. Then another. You need reassurance. You need to know they're still there. You need evidence that you haven't been abandoned.

When they finally respond: “Hey, sorry! Was in a meeting", relief floods through you. Warmth. Safety. Validation. For a moment, everything feels okay again.

But then, almost instantly, something shifts.

The closeness that felt desperately needed moments ago now feels exposing, dangerous. Vulnerable even. The intimacy you were just chasing now feels like a trap. Your body recoils. You go cold, distant, unavailable. You pick a fight. You withdraw. You ghost.

This is disorganised attachment: a nervous system caught in an impossible bind, trying to solve a problem that has no solution. Because the problem isn't this relationship. The problem is that your body learned, very early, that the people you love will hurt you. That closeness and danger are two sides of the same coin.

This isn't manipulation or game-playing. This is a survival strategy developed by a child who needed comfort from the same person who caused fear. And it's working exactly as designed for a threat that may no longer exist.

I explore this survival-driven push-pull dynamic further in why trauma bonds feel so powerful.

The Fortress Pattern (When Distance Feels Safer Than Closeness)

Other people solve the double bind differently. If closeness means danger, the answer is simple: don't get close.

You've built a life that works without depending on anyone. It's competent, independent, controlled. You don't need anyone's validation. You don't lean on people. You don't ask for help unless absolutely necessary.

On the surface, this looks like strength. And in some ways, it is. You learned self-sufficiency because you had to. But underneath the fortress—underneath the “I'm fine" and the “I don't need anyone", there's often a quiet ache. A longing for closeness that feels unreachable or too dangerous to want.

Maybe in your family, vulnerability was met with dismissal. Needs were shamed, emotions were treated as weakness or inconvenience. You learned early that expressing what you needed either led to rejection or was weaponized against you later.

So you stopped needing. And now, intimacy doesn't feel like connection, it feels like exposure. Like handing someone a loaded weapon and hoping they won't use it.

This pattern, avoidant attachment after trauma, isn't coldness. It's not lack of capacity for love. It's a body that learned to keep you at a safe distance from what once hurt. And it's keeping you safe, yes—but also profoundly lonely.

How Trauma Rewrites Your Attachment Blueprint

Here's what many people don't understand about attachment: it's not a fixed personality trait. It's a relational strategy shaped by your earliest experiences and updated based on new information.

Attachment shifts with context, nervous system state, and who you're with.

You might be secure in friendships but anxious in romantic relationships. Self-sufficient with family but clingy with a partner. Calm and steady when rested, but reactive and desperate when triggered.

This isn't inconsistency. It's your nervous system running different threat assessments depending on what's at stake. Last time I trusted like this, in this kind of relationship, I was harmed. So your body adapts, trying to protect you from repeating history.

Anxious attachment can become avoidant after betrayal. Avoidant can become preoccupied after loss. Secure can become disorganised after sustained emotional abuse. Your attachment style updates based on your relational experiences, especially painful ones.

And attachment can shift within the same relationship, hour to hour. When you're rested, connected, and grounded, you might feel secure. When you're stressed, triggered, or reminded of old wounds, your nervous system reverts to older protective strategies, even though the person in front of you hasn't changed.

What Living With Trauma-Shaped Attachment Actually Feels Like

If you've lived through complex or developmental trauma, attachment probably doesn't show up in the neat categories psychology textbooks describe. Instead, it might look like this:

Your attachment style changes depending on who you're with. Secure with friends. Anxious with romantic partners. Completely avoidant with family. Different relationships activate different wounds, different fears, different survival strategies.

You understand your pattern intellectually but can't stop reacting. You can explain exactly why you do this, you've read the articles, done the therapy homework, journaled about your childhood. You can see it happening in real time. And yet your body takes over anyway, flooding you with panic or shutting you down entirely before your rational mind has a chance to intervene.

You feel deep shame about your reactions. I'm too much. I'm too needy. I'm too cold. I'm damaged. I'm impossible to love. The shame often feels worse than the original hurt, creating a secondary wound on top of the trauma itself. This connects deeply to patterns of toxic shame from childhood.

You swing between connection and withdrawal within hours or minutes. The person who felt safe this morning feels threatening this afternoon. Your partner says one slightly off thing and your whole body recoils. Then later, you're desperate for reassurance that they're not leaving. This isn't mood swings, it's your nervous system toggling between threat states.

You experience yourself as fragmented. The part of you that wants closeness and the part that recoils from it feel like different people with incompatible needs. You're not choosing to be contradictory, you genuinely want both things at once, and it's tearing you apart.

These aren't failures. These aren't signs you're broken beyond repair. These are signs that your nervous system is still operating from a trauma-based model of relationships, still protecting you from dangers that may no longer exist.

Side by side on the trail: security, connection, and the quiet power of being close.

What Your Nervous System Is Actually Doing

The behaviours people see: the clinginess, the coldness, the volatility, the withdrawal are just the surface. Underneath is a nervous system running complex threat-detection algorithms, most of it happening outside conscious awareness.

Your body is constantly scanning for cues of safety and danger, often in ways you don't notice:

Hypervigilance: Reading micro-expressions for signs of rejection or criticism. Monitoring tone of voice. Analysing text messages for hidden meaning. This exhausting surveillance system developed because unpredictability meant danger, so your nervous system learned to look for patterns, clues, early warning signs. This can also show up in relationships as sensitivity to small behaviours that feel like betrayal.

Flooding or numbing: When emotions come, they come as overwhelm, your chest tightens, your thoughts race, everything feels too big to hold. Or they don't come at all, you go numb, disconnected, watching your own life from behind glass. Both are protective responses. Flooding is your body's alarm system. Numbing is your body's circuit breaker when the alarm is too loud.

Testing: Pushing and pulling to gather safety data. Saying things to see if they'll leave. Withdrawing to see if they'll chase. Going silent to see if they notice. This isn't manipulation, it's your nervous system conducting experiments: If I show them this part of me, will they stay? If I pull away, will they prove they actually care?

Survival responses in conflict: Fight (defensiveness, anger, blame). Flight (leaving, stonewalling, ghosting). Freeze (going blank, unable to speak). Fawn (people-pleasing, apologising for things that aren't your fault, abandoning your own needs). These aren't choices, they're reflexive responses your nervous system learned when actual danger was present.

Somatic cues: Tight chest. Nausea. Throat constriction. Restlessness. Numbness. Dissociation. Your body often knows you're unsafe before your mind does. And if you learned to ignore or suppress those signals, you might not recognize them as your body's attempt to communicate.

The behaviors others see are symptoms. The real work is happening in your nervous system, which is doing its job—protecting you. The problem isn't you. The problem is that your nervous system is still responding to yesterday's threats in today's relationships.

Beginning to Heal and Finding Safety in Connection Again

Healing attachment wounds doesn't happen through insight alone. You can't think your way out of a nervous system response. You can't logic yourself into feeling safe. Healing happens through repeated experiences of safety that slowly teach your body: This time is different.

When Relationships Become the Medicine

Healing happens in relationship, specifically, in relationships where you feel emotionally safe and where the other person can stay steady when you wobble.

This might be a therapist who doesn't take your defensiveness personally and doesn't abandon you when you test boundaries. A friend who says, “I notice you're pulling away and I'm still here", without making it about them. A partner who can hold space for your fear without needing to fix it or defend themselves.

Safety isn't perfection. It's not someone who never hurts you. It's someone who can repair when they do. Someone who can tolerate your anger, fear, or withdrawal without retaliating or disappearing. Someone who meets your nervous system's questions: Will you leave? Am I too much? Is this real? with steady, consistent presence.

Over time, these experiences create new data for your nervous system. Not through understanding, but through felt experience: Oh. Closeness didn't lead to harm this time. And the time before. And the time before that.

Learning Your Body's Language

You can't think your way out of attachment trauma, but you can learn to recognise when your nervous system is activated. And that recognition creates a tiny bit of space between stimulus and reaction.

Notice the sensations first, before the stories: My chest is tight. My thoughts are racing. My jaw is clenched. I feel the urge to run or attack or disappear or fix everything.

Then name what's happening, without judgment: I'm in a fear response right now. My nervous system thinks I'm in danger.

This isn't about stopping the response or making it go away. It's about developing the capacity to witness it without being completely overtaken by it. To say, Oh, there's that pattern again. My body is trying to protect me.

Practices that help:

Grounding: Feel your feet on the floor. Name five things you can see. Notice the temperature of the air on your skin. These bring you back to the present moment, which is where safety actually exists.

Gentle movement: Walking, stretching, shaking out your arms. Trauma lives in the body, and movement can help complete the stress cycle your nervous system started.

Breathwork: Not forcing deep breaths, but noticing your natural rhythm and maybe extending your exhale slightly. This signals to your nervous system that you're safe.

Noticing glimmers: Learning to recognise your body's cues of safety, the moments when your shoulders drop, when your breath deepens, when you feel even a little bit of ease. These teach your system what safe connection feels like.

Replacing Shame With Understanding

Shame is the enemy of healing. It keeps you stuck in cycles of self-blame, hiding your struggles, believing you're uniquely broken.

Self-compassion starts with a single recognition: These patterns once kept me alive.

Your clinginess protected you from abandonment. Your walls protected you from violation. Your people-pleasing kept you safe from rage. Your hypervigilance kept you one step ahead of danger.

These weren't failures. They were brilliant adaptations to impossible circumstances. Your nervous system developed exactly the strategies it needed to survive the relationships you were given.

The work now isn't to shame yourself for these patterns. It's to honour them for what they were, survival, while gently, carefully updating them for the relationships you're in now, where the old rules no longer apply.

Becoming Your Own Secure Base

Much of healing attachment trauma involves learning to offer yourself what you needed then and didn't receive: steady presence, unconditional worth, patience with your process, kindness when you stumble.

This isn't about affirmations or positive thinking. It's about noticing the moments when you're activated and asking: What does the frightened part of me need right now?

Sometimes it needs reassurance: You're not too much. Your needs matter. You're allowed to want closeness.

Sometimes it needs permission: It's okay to feel scared. It's okay to need space. You don't have to have it all figured out.

Sometimes it needs protection: I won't let anyone treat you that way again, including me. I'm here. I'm not going anywhere.

Over time, you become the secure base your nervous system never had. Not perfectly, you'll forget, you'll be harsh with yourself, you'll repeat old patterns. That's okay. Good enough is all that's needed. And good enough, as attachment research shows us, is actually quite healing.

Attachment Myths That Keep You Stuck

Myth 1: People with secure attachment had perfect childhoods

The Reality: Nobody needs perfect parents to develop secure attachment, just parents who were “good enough" most of the time.

Researcher Ed Tronick discovered something surprising: caregivers only need to really get it right about 30% of the time. Parents can miss the mark, get stressed, misunderstand their kid, or be unavailable 70% of the time, and the child can still grow up feeling fundamentally safe in relationships.

What matters isn't perfection. It's whether there was enough consistency, enough repair after mistakes, enough moments of “I see you and you matter" to teach that child's developing brain: people can be trusted.

People with secure attachment may have grown up poor, experienced loss, dealt with family stress, or even faced some trauma. What they had was at least one person who showed up for them emotionally, not perfectly, but reliably enough.

Myth 2: Insecure attachment means something's wrong with you

The Reality: Almost half of all people, around 40%, have insecure attachment. You're in good company.

This isn't a disorder or a defect. It's how your nervous system learned to survive in relationships that couldn't give you consistent safety. Your body did exactly what it needed to do with the resources it had.

And here's what matters more: attachment style is just one piece of who you are. It doesn't define your worth, your capacity to love, your intelligence, your creativity, or whether you can be a good partner or parent.

Plenty of people with insecure attachment build beautiful relationships and meaningful lives. They just have to be more intentional about it, learning as adults what others absorbed as children.

Myth 3: You must be secure to have a healthy relationship

The Reality: You don't need to fix yourself before you can have a healthy, loving relationship. Many people with anxious or avoidant patterns have deeply satisfying partnerships.

What makes a relationship work isn't whether both people have perfect attachment styles. It's whether both people are willing to work together to create safety, to show up during hard moments, to repair when things go wrong, to prioritise each other's wellbeing.

Someone with secure attachment can absolutely be in a toxic relationship. Someone with a trauma history can absolutely be in a healing one. The difference isn't your past, it's what you and your partner build together now.

In fact, safe relationships often become the path to healing. When someone loves you consistently and well, your nervous system gets to learn something new: maybe closeness doesn't have to hurt.

Myth 4: Insecure people can't attract secure partners

The Reality: Attachment style isn't the main reason we're drawn to someone. We fall for people because of chemistry, shared values, humour, timing, physical attraction, and the way they make us feel, countless factors beyond attachment.

Plus, your attachment style isn't the same in every relationship. You might be anxious with romantic partners but secure with friends. Avoidant with family but open with your partner. It shifts depending on the relationship and what it brings up for you.

You don't need to “become secure" before you deserve love. You need to find someone who can meet you where you are, who stays steady when you're struggling, who doesn't punish you for your fear, who's willing to build safety with you over time.

Myth 5: Attachment styles never change

The Reality: Attachment styles change. They're not locked in for life.

If you spend years in a safe, responsive relationship, with a partner, therapist, close friend, or community, your nervous system can learn a new way of being. This is called “earned security", and research shows it's just as solid as the security people develop in childhood.

The reverse is also true: someone who grew up secure can become anxious or avoidant after betrayal, abuse, or ongoing relationship stress. Their nervous system updates based on new experiences: Oh, maybe closeness isn't safe anymore.

Your attachment style isn't who you are. It's how your nervous system currently approaches relationships based on everything it's learned so far. And just like any learned pattern, it can change with new experiences, safety, and time.

Expanding Your Window of Safety

Healing doesn't mean becoming perfectly secure. It means:

Expanding your window of tolerance for discomfort in relationships

Recognizing when you're in a trauma response more quickly

Repairing ruptures instead of letting them destroy the connection

Staying present with yourself and others, even when your body says run

Building trust slowly, carefully, that safety can exist alongside closeness

This work is slow. It's non-linear. There will be setbacks that feel like starting over. That's not failure, that's how nervous systems learn. Through repetition, safety, and time.

You're not broken. You're not too much or too difficult or impossible to love. You're a person whose nervous system learned to survive in relationships where love and fear were tangled together. And now you're learning something new: that closeness doesn't have to hurt. That you can be seen and still be safe. That your needs aren't a burden.

This is the work. And it's worth it.

Related Reading

More resources to help you understand shame, safety, and healing:

You Are Not Your Adaptation

Your attachment style is not your identity. It's not a life sentence or a character flaw.

It's a snapshot of how your nervous system learned to survive in the relationships you were given, often before you had language, choice, or any other option.

Those strategies were brilliant then. They kept you alive. They helped you navigate impossible situations with developing brains and no power.

But you're not there anymore. And healing begins the moment you stop blaming yourself for how you adapted and start gently, patiently teaching your body that safety is possible again.

Need Support?

Melbourne-based trauma-informed therapy for individuals navigating attachment, estrangement, and complex relational wounds.

Kat O’Mara

📧 kat@safespacecounsellingservices.com.au

📱 0452 285 526

Attachment is the pattern your nervous system uses to connect, protect and relate, shaped by early experiences and adaptable over time.

Related Reading

More resources to help you understand shame, safety and healing.